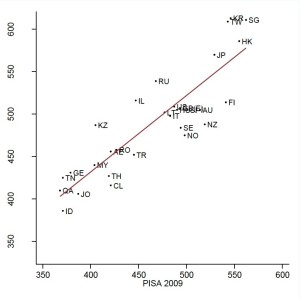

About six months ago I released a paper (https://johnjerrim.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/australia_asia_paper.pdf) discussing reason for East Asian success in PISA, focusing largely upon the role of home background and culture. I have been somewhat overwhelmed by the number of people who have shown an interest in this paper and have contacted me about this work since. Today I will present some evidence on the other side of the story – the ‘impact’ of East Asian teaching methods on children’s mathematics test scores.

Over the last two and a half years I have been evaluating the ARK ‘Maths Mastery’ programme along with Anna Vignoles from the University of Cambridge (http://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/people/staff/vignoles/). This introduced a Singaporean inspired ‘mastery’ teaching approach into a selection of England’s primary and secondary schools, with the impact evaluated via a Randomised Controlled Trial methodology. The Education Endowment Foundation reports can be found here (http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/projects/mathematics-mastery/) and the subsequent academic paper here (www.johnjerrim.com/papers).

The two trials were of reasonable quality, and produced some interesting results. They both pointed towards a small positive effect, though neither quite reached statistical significance independently. When combining the evidence across the two trials, we found children exposed to the programme made around a month more progress in mathematics than those who did not. To put this another way, the programme would move a child at the 50th percentile (i.e. ranked 50th in mathematics within a school of 100 children) up to around 47th.

There is of course quite a bit of uncertainty surrounding this result. For instance, it is not clear how far one can extrapolate results from this trial to the wider population, while the confidence intervals suggest that the ‘true’ effect size could be a lot bigger (double) or smaller (essentially zero) than we report. We nevertheless feel that the results provide some interesting insights, particularly given policymakers interest in East Asian teach methods, given these countries strong performance in PISA.

To begin, there is no escaping that the effect size we found was small. This suggests that introducing such methods would be unlikely to springboard England to the top of the PISA rankings. Indeed, as I have noted previously (https://johnjerrim.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/australia_asia_paper.pdf), there are likely to be a lot of other factors in these countries at play.

Yet, at the same time, effects of this magnitude are also not trivial, particularly given the low cost per pupil. For instance, effects of a similar magnitude were reported for The Literacy Hour (http://cee.lse.ac.uk/ceedps/ceedp43.pdf) – which many consider to be a good example of a low-cost intervention that was a success. Moreover, our trials only considered the impact of introducing such methods after just one year (the first year such methods were used in these schools). But programmes like Maths Mastery are meant to develop children’s skills over several years, which may result in bigger gains. However, there is currently no empirical evidence available for us to judge whether this is indeed the case or not.

Given the above, our advice is that policymakers should proceed with their investigations into the impact of East Asian teaching methods, while also exercising caution. In particular, the empirical evidence currently available does not have sufficient scope or depth to base national policy upon. But there are perhaps some positive signs. What is now needed is further research establishing the long-run impact of such methods after they have been implemented within schools for several years, and after teachers have more experience with this different approach.